in Strength & Conditioning

Hop on Instagram and you will be bombarded with pictures of “evidence-based” coaches explaining the “optimal” way to lose fat, build muscle, and improve fitness.

But really, along with being a buzzword used across the industry, what does being “evidence-based” really mean?

Evidence based practice can be defined as a systematic process whereby decisions are made using the best available evidence.

This is done with the intent to remove subjective bias and unfounded beliefs from the decision making process, thus providing the best available service to your clients.

It is important to highlight that while sources of evidence absolutely include peer reviewed research, they also include:

- Anecdotal evidence

- Practitioner experience

- Feedback from clients and patients

Which is what too many people seem to forget.

See, if you are writing a new client program, the peer reviewed research provides a fantastic place to start because it highlights what works for most people, most of the time.

But it is important to remember that research typically provides group level data — and may not always provide the best guidance for an individual.

Everyone is different

To hammer this point home I want to highlight a fantastic 2010 paper by Erskine and colleagues.

In this study 53 untrained men were put on a progressive weight training program that involved performing leg extensions three times per week for nine weeks, where load gradually progressed on a weekly basis.

At the group level, knee extension strength increased by 26% over the nine weeks, while quadriceps size increased by 6%.

Not too shabby.

However, when you look at the individual data, things get a little more interesting…

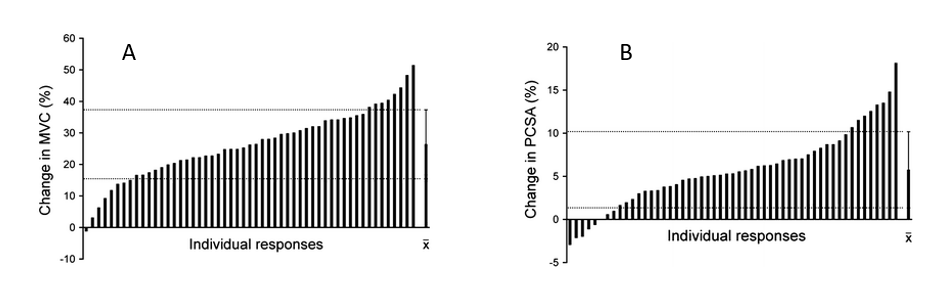

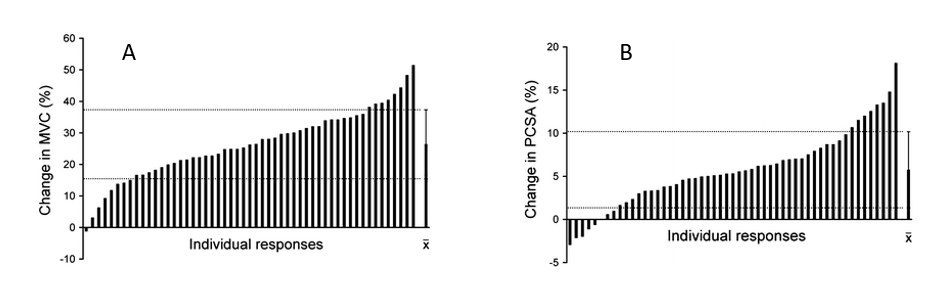

Image adapted from Eskrine et al., (2010): A) The range of individual changes in MVC [strength] relative to baseline values, B) The range of individual changes in PCSA [quad size] relative to baseline values

Looking at this data, you can see that while the group average increases in strength were 26%, the individual variance ranged from -1% all the way up to 52%.

Similarly, while the average increase in size was 6%, one person saw a -3% change in size, while another grew by an absurd 18%.

And just to be clear, that is not a typo — some people actually got weaker and smaller following a program that aligns pretty well with most resistance training recommendations.

So, where does this leave us?

Being truly evidence based

With this in mind, actually being “evidence based” means using science to formulate a starting point — because that is what will work with most people, most of the time.

But that is not where it ends.

This needs to be combined with your anecdotal experience and the individual response from the human in front of you to ensure that a good rate of progress is maintained.

If you are doing everything by the book and someone simply is not improving, then staying the course is not “evidence based” because you are ignoring the evidence right in front of your eyes.

Similarly, if the research suggests that you should be using a back squat to optimise sprint performance, but anecdotally you know that taller athletes tolerate front squats better, choosing front squats is still “evidence based.”

The key is ensuring you are not married to your beliefs and happy to integrate the evolving literature into your decision making process, then adjusting as necessary based upon your experience as a practitioner and the experience of your clients.

In the wise words of Jake Remmert, being evidence based is not being “science only”.

As any good practitioner knows…

Finding an accredited exercise professional

READ MORE LIKE THIS,